It is almost exactly half a century to the day since the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated in a motel in Memphis, Tenn., and in that span he has been apotheosized into something close to legend.

So much so, in fact, that we run the risk of not spending enough time with the actual man, of not knowing as much as we should about the controversial final years that reveal an individual more radical, and more disregarded, than he has been remembered.

Remedying that situation is the goal of the exceptional documentary “King in the Wilderness,” which employs a simple and straightforward method to extraordinary effect.

As directed by Peter Kunhardt, and playing at Laemmle’s Playhouse in Pasadena before airing on HBO on April 2, the film made the decision to, in its own words, “have [King’s] friends sit down to recall the last years of his life.”

Aside from the extraordinary nature of those years, several factors are key to the film’s success with what is basically a talking heads formula.

For one thing, those friends turn out to be uniformly articulate and insightful, and the unadorned interviews are conducted by two people, Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Taylor Branch and writer Trey Ellis, who know this period and the people involved intimately.

Interviewees include celebrities Joan Baez and close friend Harry Belafonte as well as movement insiders ranging from public figures like Jesse Jackson, Andrew Young and John Lewis to lesser known advisors like Clarence Jones, King’s personal attorney.

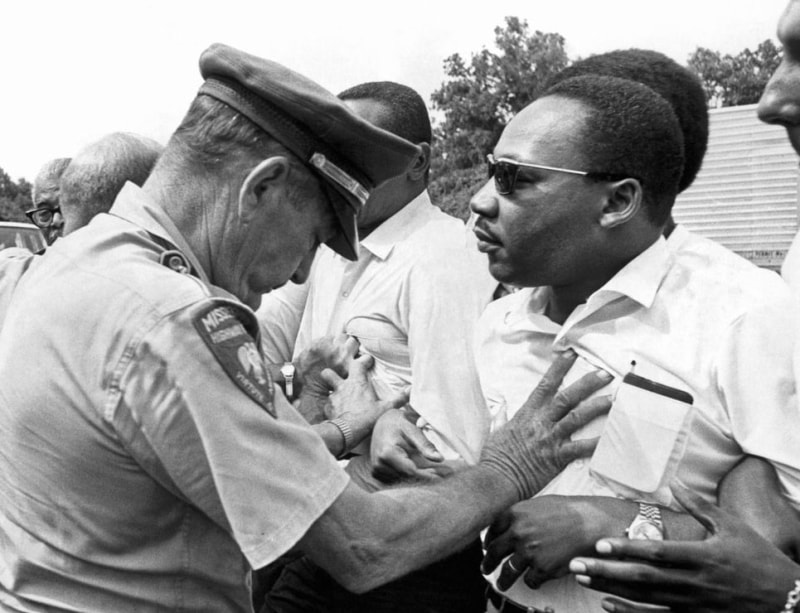

These interviews are movingly stitched together by editors Maya Mumma and Steven Golliday and intercut with smartly chosen newsreel material, including clips from the astonishing, almost prophetic “I’m not fearing any man, mine eyes have seen the glory of the coming of the Lord” speech King gave the night before he was assassinated.

What’s particularly compelling about this material is that all witnesses saw the same transformation in King. As a result of, says Young, “trying to redeem the soul of America from the triple evils of racism, war and poverty,” King found himself, in Belafonte’s words, “unprepared for the villainy he saw in the world.”

Sums up Jones, “the last 18 months before the assassination was the most difficult time of his life.”

Though it focuses on that year and a half, and starts with a heartbreaking story told by friend Xernona Clayton of how King’s young sons uncharacteristically tried to prevent him from taking that last trip to Memphis, “King in the Wilderness” starts with the cataclysmic events that took place three years before his death.

Stunned by the violence that erupted in Watts in August 1965, King visited the area (we see him heckled in a brief clip) and decided to engage with issues like housing, education and unemployment in the North.

That led, in January 1966, to King’s moving into what newspapers described as “a Chicago slum flat,” initially without electricity or heat during a winter where the temperature dropped to 16 below.

King’s reception in the city was just as frosty. The racial hypocrisy here was extreme, the situation less predictable than the South, the hostility of white residents more intense than expected.

We hear a secretly recorded Chicago Mayor Richard Daley telling President Lyndon Johnson that King was “a goddamn faker,” and hear black ministers, part of Daley’s patronage system, demand that King leave town. “Chicago,” remembers Belafonte, “was a huge awakening to him.”

At the same time, King was pulled back to the South in June 1966 when James Meredith, the student who integrated the University of Mississippi, was shot.

That trip exposed profound differences of opinion with Stokely Carmichael, the head of the Student NonViolent Coordinating Committee, or SNCC, who emphasized black power and in no way believed in nonviolence as a moral imperative the way King did.

Also putting pressure on the minister was the student left, who wanted him to take a stand against the Vietnam War. When King did, saying “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today is my own government,” he was attacked on all sides. “He died,” Clayton pointedly comments, “of a broken heart.”

Still, King did not waver in his commitment to eradicating poverty, founding the Poor People’s Campaign that led to his fatal trip to Memphis to support a sanitation workers strike.

As horribly tragic as King’s death was at the time, it seems worse now, when leaders of his stature are painfully thin on the ground. Though this film is simple to summarize, to understand and experience the powerful emotional charge “King in the Wilderness” conveys, it simply must be seen.