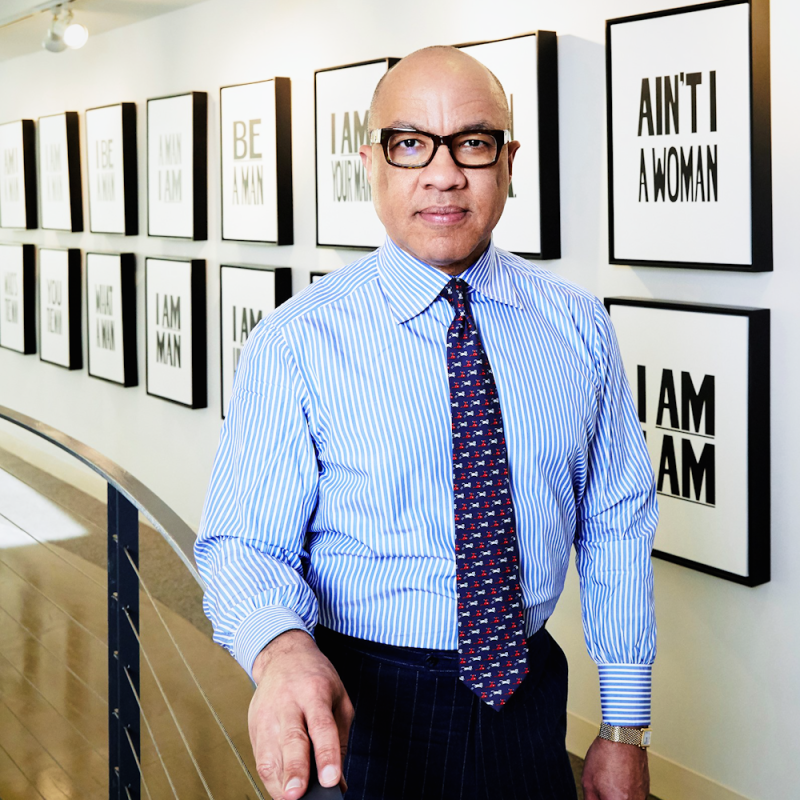

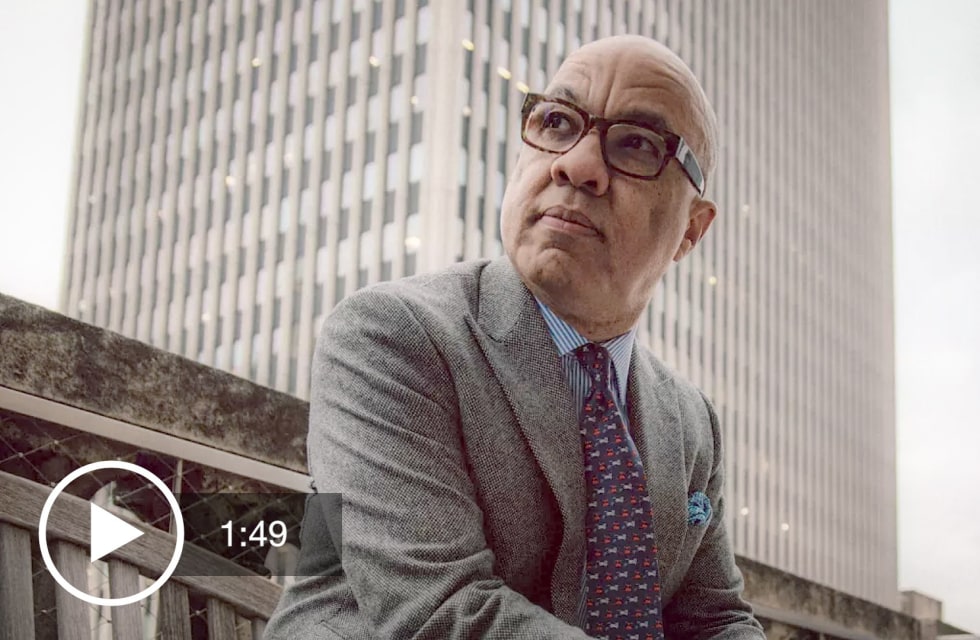

DARREN WALKER INTERVIEW

PORTIONS USED IN: THE THREAD SEASON ONE

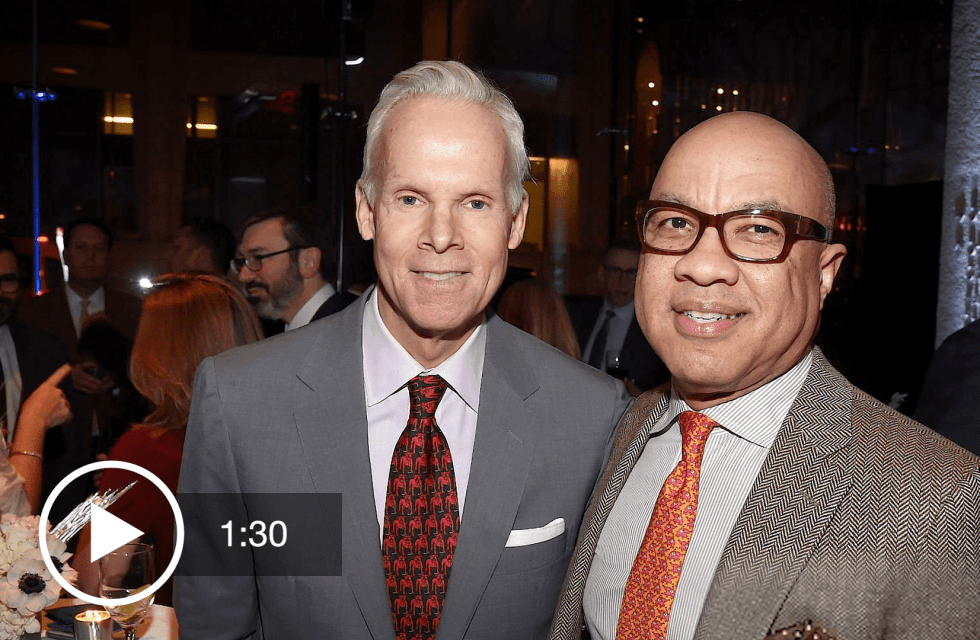

Darren Walker, President, Ford Foundation

Interviewed by Noah Remnick

Total Running Time: 33 minutes and 55 seconds

START TC: 00:00:00:00

ON SCREEN TEXT:

DARREN WALKER

PRESIDENT, FORD FOUNDATION

Darren Walker

President, Ford Foundation

00:00:19:00

NOAH REMNICK:

So since becoming president of the Ford Foundation, you've been tackling inequality. I'm wondering how you would define inequality and how you came to see it as the

defining social problem of our time?

DARREN WALKER:

Well, inequality is the defining social problem of our time because inequality is harmful to hope. Inequality makes hope, makes opportunity less a reality. And with inequality comes hopelessness, a growing sense of a lack of opportunity, which leads, in a democracy, to behaviors by the citizenry that are ultimately harmful to that very democracy. And so we believe at the Ford Foundation, because our mission is in part to strengthen and promote democracy, that inequality is our harm.

NOAH REMNICK:

So a few years ago you released a book called From Generosity to Justice. I'm wondering what motivated you to write it, and what does it mean to move from generosity to justice?

00:01:37:00

DARREN WALKER:

I learned about American philanthropy first by reading Andrew Carnegie's seminal essay, his 1889 The Gospel of Wealth in which he outlined the contours of American philanthropy, what men like himself should do with their wealth. He talked about charity, generosity. He talked about religious reasons, moral reasons for giving. I was also inspired many years later, by the words of Dr. Martin Luther King, which he wrote in 1968 about philanthropy. About philanthropy, Dr. King in 1968 said the following, "Philanthropy is commendable, but it should not allow the philanthropist to overlook the economic injustice which makes philanthropy necessary." So what Dr. King was saying was something in contrast to Carnegie's words. He was saying that yes, generosity and charity are important and necessary, but not enough. Dr. King said that the work of philanthropy must be about dignity and justice, not just charity and generosity.

NOAH REMNICK:

As the person at the top, deciding what causes to prioritize, what goes through your mind? That strikes me as this gigantic, almost existential dilemma.

00:03:13:00

DARREN WALKER):

What goes through my mind leading the Ford Foundation is my accountability and responsibility to the mission, to the demands of our time, to being effective and relevant and having impact, ultimately. And what are the pathways to impact? How does one think about strengthening democracy sitting here at the Ford foundation?

NOAH REMNICK:

You've made a point of discussing how your early years continue to shape your work. I'd love to hear how would you would describe your childhood.

DARREN WALKER:

I was very, very lucky. I lived as a boy in a country that believed in my potential. I was born in a small town in Louisiana, in a charity hospital. My mother, fortunately, moved my sister and myself to a small community in Liberty County, East Texas, a town called Ames, Texas. It had about 1000 people living in that community at the time. We lived on the dirt road in a little shotgun house. And I, on one occasion, in 1965 had a life changing experience. We were visited by a woman talking about a new government program that President Johnson was instituting that summer called Head Start. So I was very lucky to be in the inaugural class of Head Start in Ames, Texas in 1965.

NOAH REMNICK:

Tell me a bit about your parents and the influence that they had on you as a boy and the ways that they've continued to shape your life today.

00:05:02:00

DARREN WALKER:

Well, I never knew my father, so I can't really opine on him. But I can certainly say, knowing my mother very well, over all these years that she left an indelible mark on my life because she was supportive of me in every way, although she didn't have the means to always provide for luxury. We were never poor in my mind. We always felt like we had what we needed. So I was lucky. I think when I reflect on my work here at the Ford Foundation today. And I reflect on my work, what prepared me. When I was a 13 year old boy, I got my first job. I was a busboy in a restaurant. And what I learned from that job, first is about hierarchy. When you're the busboy, you and the dishwasher are the lowest of people in the organizational hierarchy of a restaurant. And when you are the bus boy, your job is to, first and foremost, be invisible. To go around the room and as discreetly and quietly as possible, take away the things that other people discard, the things that people reject and don't want.

00:06:40:00

DARREN WALKER:

And you're to do that without in any way being visible. And often to the guests, I was invisible. I wasn't acknowledged, I wasn't necessarily extended any real dignity or recognition for the fact that I was a human being standing in front of someone. And when I think about the problems of the world today and our work at Ford, I think about what it feels like to be invisible, to feel that others don't see your own humanity and others certainly don't extend dignity to you. There are too many people in the world today who feel this way. And our work at Ford is to ensure that as many people as possible in the world experience dignity.

NOAH REMNICK (01:08:10):

But you've discussed before the fact that growing up several of your cousins ended up entangled in the criminal justice system. I'm wondering if you could talk a little bit about that and how it shaped your understanding of yourself and the world around you?

DARREN WALKER (01:08:28):

Well, there's no doubt that as a boy growing up, I had wonderful experiences with my cousins. I recall playing in open yards with them. I recall just doing the things that young boys and girls do with their cousins and siblings, especially if you're a big family and small towns. But I also remember the divergence in our journeys because I didn't live in the towns where they lived in Louisiana. And I had a very engaged mother in my life. I saw what happened in their communities. I saw the widespread-seeming, being swept up in a system, a system that had low expectations for them, a system that provided very weak educational opportunities and very little, if any, economic opportunity.

00:09:09:00

DARREN WALKER:

So there's no avoiding the fact that by the time I was a young adult, my journey and the journey of so many of my cousins, for example, diverged significantly. I was in college and many of them were in prison. And that is very painful because they were as talented as I. They, I think, with the right support could have also been in college and not in prison. But I believe they also got caught up in systems, systems and structures that were designed with race in mind. And race and class geography, intersected in their lives in ways that made it very, very difficult for them to advance.

NOAH REMNICK:

What did you learn about mortality that stuck with you?

DARREN WALKER:

I think one of the things you learn as a child when you experience trauma, is you begin to master compartmentalization. Compartmentalizing is a critical ingredient to success. If one is to stay focused and clear in your aspirations, your ambitions and your goals in life. And I absolutely learned that as a young child and it's something for good and bad, that as an adult, I realized I know a lot about.

NOAH REMNICK:

Did you ever experience fear as a child? Has fear played a role in your life?

00:11:06:00

DARREN WALKER:

I never experienced fear. There was no doubt there were times I experienced physical fear, for sure. But I was always clear that I wanted to do better. I was motivated more by a desire to please than I was by fear if I'm to be honest. One of the things that you learn as a child is, when you do something good or that is perceived as positive, it pleases your parents, it pleases your family. And one of the things that kids like me learned early on was how to please our parents. You pleased your parents when you did well in school. I please my mom when she'd go to the beauty parlor and someone would say, "I saw Darren and he won this award," or this very positive thing happened. Well, she glowed with pride. So I think I was more motivated by that than I was a fear of anything.

NOAH REMNICK:

Were there any events in your early life that required you to show courage and what do you see the role of courageousness in your life and work today?

DARREN WALKER:

Well, there's no doubt that courage is in short supply today. And that's in part because courageous leadership is not always rewarded. Indeed, many of our leaders are discouraged from being courageous because the consequences of courageous leadership can be ending of a career, can be public scorn or ridicule, loss of status, loss of job. To be courageous today requires a sense of self-awareness and purpose and a willingness to live with the consequences.

00:13:41:00

DARREN WALKER:

As a child growing up, there were absolutely times when I felt it was important to be courageous, to take a side, to do something that would not necessarily be popular with either side. I can think about times when it was important to build bridges, to build bridges between the white students in my high school and the Black students in my high school, who at times were at odds. I always felt that my role was to be a bridge builder, was to not benefit from the division in our school but to see the possibility that could come from our coming together. And for me, I think about today, leaders who are disincented from doing that. Who are indeed incented and encouraged and rewarded for dividing us. Rewarded for not building bridges but building walls. And I don't see that as courageous. I see that as the easy way out. I don't see that as courageous leadership. I mean I just think we need more of it.

NOAH REMNICK:

So you grew up without a whole lot materially, but one thing that seems to have really dramatically changed the circumstances of your life as you mentioned, was the support of good old fashioned government programs. How did benefiting from those programs inform you? And how did we get to a place where that vision of America seems so distant now?

00:15:39:00

DARREN WALKER:

Well, I was very lucky to grow up in a country that believed in me. And the way a country commits itself to its people, in part, is committing itself to the potential of the human capital in its society, especially that human capital that has historically not been able to be fully realized, the potential to be fully realized. And so the Head Start program, public schools, the Pell Grant, private scholarships. All of these investments made it possible for me to get on the mobility escalator and ride it as far as my talent and my ambition could take me. And that is something I wish for every American. Unfortunately, too many people in this country believe that government is not serving their needs. That may be true, but it is also true that there has been an effort to discredit the idea of government, the very idea of the democratic institutions that makes it possible for our democracy to thrive.

00:17:16:00

DARREN WALKER:

So we have to take that on. We have to acknowledge the threat posed by those who would seek to destroy the institutions that our democracy relies on. And that is why investing in hope is so important. Hope is the oxygen of democracy. When we have more hope, we will have a better democracy. But in order to generate hope, people have to believe in something. Part of what they have to believe in, in a democracy, is in their actual government. And I think what we are seeing today in America is a contestation of the idea of government. My hope is that democracy wins.

NOAH REMNICK:

After law school, you moved to New York City where you dabbled in law and then finance for a while. You said that no small reason you took those jobs was financial security. But when did you come to realize that you wanted something more out of your professional life, that you wanted to make not only a dollar, but a difference?

00:18:37:00

DARREN WALKER (01:19:38):

I always knew that my life's journey would not be in the for-profit world. For me, I was aware from the beginning that my time, on Wall Street for example, had an expiration date. That I would not be happy simply waiting for the bonus each year and piling up money. And so for that reason, I was always engaged outside of work in the community. It's how I first became involved in Harlem. Because I volunteered at the Children's Storefront School up on 129 street while I was working as a banker at UBS. And ultimately, the pull of Harlem, the chance to do work that was really meaningful to me became compelling. And I, after a few years, made the jump and I never looked back. I've never been happier. I certainly never regretted leaving Wall Street.

NOAH REMNICK:

So fast forward to 2013 and you're named the President of Ford. Was that daunting, thrilling? How did you begin to settle into the role and set your priorities?

00:20:06:00

DARREN WALKER:

Well it was a huge, thrilling moment for me. In some ways it was like coming home. So many of the investments that were made in me. The Pell Grant, Head Start were programs of the Ford Foundations. They were pilot programs of the Ford Foundation in the 1960s. I worked for a community development corporation, which was also a creation of the Ford Foundation. And so when I came to Ford, in some ways, it felt like coming home. This institution is a remarkable place with unparalleled heritage in the area of social change, social progress and human achievement. To have the privilege of serving this institution was something I could never have imagined. And so I was humbled. And every day I am humbled and challenged to rise to the opportunity and the expectation of service.

NOAH REMNICK:

What have been some of the toughest choices you've had to make at Ford. And on the flip side, what have been some of your proudest moments here?

DARREN WALKER:

I think some of the most difficult choices are the programs that you decide to wind down. I mean, there are things that the Ford Foundation supported for many years that we started to wind down. Our work in K through 12 public education is probably the most prominent example. Ford, for decades, had been a leader in funding K through 12 education reform in America. But over time, our investments and our impact became limited.

00:22:15:00

DARREN WALKER:

And we took the time in 2013 to review our work and those investments and came to the determination that we weren't having the kind of impact that we desired. And that there were other foundations who had come into the space and were indeed having more impact and investing more. So we made the decision to bring that work to a close. It was very controversial. It remains controversial to this day. In part because people understand that public education is a critical ingredient to mobility opportunities for low to moderate income, urban and rural Americans. We recognize that too, but for us that wasn't the question. The question for us was what are the best and highest uses of our philanthropic dollar for social change? And so we took some of those funds and invested them in criminal justice reform and addressing issues of misinformation and disinformation in this new digital era where there was very little foundation funding and yet the impact, the harm that could be done to our democracy and to our education systems were real.

NOAH REMNICK:

So it's more than okay, obviously, if you'd rather not talk about this, but I'd be remiss not to ask you about David. I'd love to hear a little bit about him, and your relationship and how he changed your life.

00:24:04:00

DARREN WALKER:

Well, David Beitzel came into my life almost 30 years ago. He was a remarkable man from a very different background, very different personality, but a person of remarkable integrity and character. He taught me about everything I know in the arts, especially the visual arts. David taught me what love looks like. I didn't really know what love looked like or felt like until I met David Beitzel. And his death was sudden and I… every day miss him. And the grief that I feel I know is a function of the love I had for him. And I'm lucky, though, because David Beitzel gave me enough love to last a lifetime. And when you're lucky enough to have that happen to you, you live every day with gratitude.

NOAH REMNICK:

The tragedy of his death was so senseless and was so unexpected. How did you push forward after that?

DARREN WALKER:

The good news is when you are healing from that kind of profound loss, there are things that make it possible to heal. And for me, I had the full checklist of those things. First family, David's family and I were and are very close. Second is, the state of your relationship with him when he died. I was very lucky because David loved me so much, literally until his last breath, and I felt that. I was lucky because I had friends and I was lucky because I had a fantastic meaningful career. Not just a career, but a calling.

00:26:38:00

DARREN WALKER:

And so the healing process for me has been, all things considered, relatively easy because I didn't have a lot of the demons and things that are suppressed and that leave you wishing you had done something different. I know David knew how much I loved him and I felt that from him. And so I don't have any regrets, which is another way that allows for healing. And so while I know that my life will never be the same, because it won't, and it hasn't been since he died, I also know that I am incredibly lucky, incredibly fortunate and blessed. And I feel that every day.

NOAH REMNICK:

You obviously gained a great deal of wisdom during your life and work. I'm wondering if there's one lesson or observation that you've learned above all others?

00:27:48:00

DARREN WALKER:

Hmm. I think the lesson for me is something that I was taught about being gracious and generous. I was told this at a very young age, and it's been something that has stayed with me as a guiding principle, a north star for my own comportment. And for the moments when I find myself feeling angry, or selfish, or egotistical or self-centered, or indifferent, I'm reminded that people who live with those qualities are not happy people. And I know because it's so true. Grace and generosity are critical to happiness in life. I find that I am happier when I extend grace and generosity to others. And when I don't let the negative things crowd that out. And it's so easy today to let those negative thoughts crowd out the goodness, the light. It's so easy during these dark times to let the darkness overtake your psyche, your emotions. But I always go back to the two G's and I don't mean Gucci, Noah.

NOAH REMNICK:

You've often returned to the theme of democracy. I'm wondering what is so central, why is that so central to your work here at Ford and what is its power and importance?

00:30:00:00

DARREN WALKER:

Henry Ford the second reimagined the Ford Foundation's mission in the 1950s. In part, it was restated to focus on strengthening democracy and democratic practice. Democracy, in my view, is the greatest way a society can be organized. It is the greatest aspiration of a people. In the United States, democracy is even more rare because our aspiration is to have a multiracial, pluralistic democracy. That may not have been the idea of our founding fathers, but they indeed did create the mechanisms, the legal foundations for a multiracial, pluralistic democracy. And I believe that experiment is worth fighting for. And at the Ford Foundation, that is what we do. We are freedom fighters for democracy because we believe that democracy is our future and that it is worth fighting for, but that we cannot take it for granted, that we cannot presume that it will exist merely because we wish it to. We have to invest in democracy, in democratic institutions. And in ensuring that everyone participates, democracy cannot be parsed out. It can't be rationed. It must be available for everyone. And we believe this is our work.

NOAH REMNICK:

So lastly, you're 62 years old now. Does time seem to be passing by quickly for you? Are you enjoying the process of getting older?

00:32:22:00

DARREN WALKER:

Well no one wants to get older. Let's be clear. None of us wants to get older. I think the question is, can we, as we get older, embrace the pleasures, the privilege of getting older but recognizing that our time is running out and therefore asking ourselves, what am I doing with the time I have left? What am I doing with the privilege that I've accreted over these years? What am I doing with the influence, the money, the access to power and networks? What am I doing to leverage that to help others? So for me, one of the privileges of being 62, being the president of the Ford Foundation, is that it gives me access, access that I would otherwise not have. My job is to use that access, to use those networks to remind people of what's important, or at least what I think is important. What we think here at the Ford Foundation is important. And that is, working for a more just, fair and equitable society.

END TC: 00:33:55:00